Samir El Khanza

GEM-DIAMOND doctoral fellow

ESR 10 – Socio-economic contestation turned into democratic conflicts? EU comprehensive trade agreements in front of parliaments: the CETA CASE

Samir is a Marie Skłodowska Curie Fellow at Luiss, Laval University and ULB. Passionate about the EU decision-making process and international trade agreements, his research will focus on how contestation can affect the EU’s ability to conclude comprehensive trade agreements.

Influencing the European trade policy-making process?

National parliaments’ role in the ratification, entry into force and implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

Supervisors

- Cristina Fasone

- Richard Ouellet

- Nathalie Brack

Research abstract

Research Question(s)

Research Hypothesis(es)

2. Greater parliamentary contestation, driven by heightened politicization, perceptions of democratic deficit, legitimacy concerns, and interpretations of the Rule of Law, motivates domestic parliaments to assert their positions in EU trade policy. As a result, they can more strongly shape or constrain the EU’s ability to conclude comprehensive trade agreements.

Personal Research Bibliography (So Far)

• Auel, K., 2007. Democratic accountability and national parliaments: Redefining the impact of parliamentary scrutiny in EU affairs. European law journal, 13(4), pp.487-504.

• Auel, K., and Raunio, T., (2014) Debating the state of the union? Comparing parliamentary debates on EU issues in Finland, France, Germany and the United Kingdom. The Journal of Legislative Studies 20(1), pp. 13–28.

• Auel, K., Eisele, O. and Kinski, L., 2016. From constraining to catalysing dissensus? The impact of political contestation on parliamentary communication in EU affairs. Comparative European Politics, 14, pp.154-176. At p.156.

• Auel, K., Rozenberg, O. and Tacea, A., 2015. To scrutinise or not to scrutinise? Explaining variation in EU-related activities in national parliaments. West European Politics, 38(2), pp.282-304. At p.287.

• Bache, I., Bartle, I. and Flinders, M., 2016. Multi-level governance. In Handbook on theories of governance (pp. 486-498). Edward Elgar Publishing.

• Beetham, D. and Lord, C., 2014. Legitimacy and the European union. Routledge.

• Bellamy, R. and Kröger, S., 2016. Representation and Democracy in the EU. Routledge.

• Benz, A., 2000. Two types of multi‐level governance: Intergovernmental relations in German and EU regional policy. Regional & Federal Studies, 10(3), pp.21-44. At p.41.

• Bollen, Y. (2018). EU trade policy. In Handbook of European Policies. Edward Elgar Publishing. P.8

• Bollen, Y., 2018. The domestic politics of EU trade policy: The political-economy of CETA and anti-dumping in Belgium and the Netherlands (Doctoral dissertation, Ghent University).

• Bollen, Y., Gheyle, N. and De Ville, F., 2016. From nada to Namur: national parliaments' involvement in trade politics, the case of Belgium. In State of the Federation.

• Bongardt, A. and Torres, F., 2022. What have we learned and how is EU trade policy to cope with new challenges?. Perspectivas: Journal of Political Science, 27, pp.148-157. At p.152.

• Brack, N. and Costa, O., 2018. Democracy in parliament vs. democracy through parliament? Defining the rules of the game in the European Parliament. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 24(1), pp.51-71.

• Brack, N., Coman, R. and Crespy, A., 2019. Unpacking old and new conflicts of sovereignty in the European polity. Journal of European integration, 41(7), pp.817-832.

• Bradford, A., 2020. The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford University Press, USA.

• Bradley, C.A. ed., 2019. The Oxford handbook of comparative foreign relations law. Oxford Handbooks.

• Bran, F., Bodislav, D.A. and Rădulescu, C.V., 2019. European Multi-Level Governance. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 8(5), pp.66-75. At p.67.

• Broschek, J. and Goff, P.M., 2022. Explaining Sub‐Federal Variation in Trade Agreement Negotiations: The Case of CETA. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 60(3), pp.801-820. At p. 802.

• Campbell, M., 2012. The democratic deficit in the European Union. In Claremont-UC Undergraduate Research Conference on the European Union.

• Chamon, M. and Govaere, I., 2020. EU External Relations Post-Lisbon: The Law and Practice of Facultative Mixity (Vol. 16). Brill.

• Christiansen, T., 1997. Tensions of European governance: politicized bureaucracy and multiple accountability in the European Commission. Journal of European Public Policy, 4(1), pp.73-90.

• CJEU, ‘The free trade agreement with Singapore cannot, in its current form, be concluded by the EU alone (Press Release)’, (2017) No/52/17.

• CJEU, C-137/12, Commission v. Council, EU:C:2013:675.

• CJEU, Case C-22/70, Commission v Council.

• CJEU, Case C-284/16 Slovak Republic v Achmea (2018) EU:C:2018:158, para 60;

• CJEU, Opinion 1/17.

• CJEU, Opinion 2/15.

• CJEU, Opinion in Case C-13/07, Commission v. Council.

• CJEU. Parliament v. Council (Mauritius), 2014, para. 71

• Conconi, P. and Perroni, C., 2002. Issue linkage and issue tie-in in multilateral negotiations. Journal of international Economics, 57(2), pp.423-447.

• Conconi, P., Herghelegiu, C. and Puccio, L., 2021. EU trade agreements: To mix or not to mix, that is the question. Journal of World Trade, 55(2).

• Costa, O. and Brack, N., 2013. The role of the European Parliament in Europe’s integration and parliamentarization process. In Parliamentary Dimensions of Regionalization and Globalization: The role of inter-parliamentary institutions (pp. 45-69). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. At p.6.

• Costa, O., 2019. The politicization of EU external relations. Journal of European public policy, 26(5), pp.790-802.

• Council of the EU, ‘EU-Singapore: Council adopts decisions to sign trade and investment agreements (Press Release)’, (2017) 563/18.

• Cremona, M., 2017. A quiet revolution: The Common commercial policy six years after the Treaty of Lisbon.

• Crespy, A. and Parks, L., 2017. The connection between parliamentary and extra-parliamentary opposition in the EU. From ACTA to the financial crisis. Journal of European Integration, 39(4), pp.453-467.

• Crespy, A. and Rone, J., 2022. Conflicts of sovereignty over EU trade policy: a new constitutional settlement?. Comparative European Politics, 20(3), pp.314-335. At p.323.

• Crum, B. and Fossum, J.E., 2009. The Multilevel Parliamentary Field: a framework for theorizing representative democracy in the EU. European Political Science Review, 1(2), pp.249-271.

• Crum, B., 2022. Patterns of contestation across EU parliaments: four modes of inter-parliamentary relations compared. West European Politics, 45(2), pp.242-261.

• Dąbrowski, M., Bachtler, J. and Bafoil, F., 2014. Challenges of multi-level governance and partnership: Drawing lessons from European Union cohesion policy. European Urban and Regional Studies, 21(4), pp.355-363.

• De Bièvre, D. and Poletti, A., 2013. 2 The EU in trade policy. EU Policies in a Global Perspective: Shaping or taking international regimes?, p.20.

• De Bièvre, D. and Poletti, A., 2020. Towards explaining varying degrees of politicization of EU trade agreement negotiations. Politics and Governance, 8(1), pp.243-253.

• De Bièvre, D., 2018. The paradox of weakness in European trade policy: Contestation and resilience in CETA and TTIP negotiations. The International Spectator, 53(3), pp.70-85.

• De Wilde, P. and Raunio, T., 2018. Redirecting national parliaments: Setting priorities for involvement in EU affairs. Comparative European Politics, 16, pp.310-329. At p.314.

• De Wilde, P., Leupold, A. and Schmidtke, H., 2016. Introduction: The differentiated politicisation of European governance. West European Politics, 39(1), pp.3-22.

• Dirk De Bièvre (2018) The Paradox of Weakness in European Trade Policy: Contestation and Resilience in CETA and TTIP.

• Dür, A., Eckhardt, J. and Poletti, A., 2020. Global value chains, the anti-globalization backlash, and EU trade policy: A research agenda. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(6), pp.944-956. At p.947.

• Dür, A., Hamilton, S.M. and De Bièvre, D., 2024. Reacting to the politicization of trade policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 31(1), pp.1-19.

• Eising, R. and Kohler-Koch, B., 1999. A comparative assessment. The transformation of governance in the European Union, 12, p.267.

• Eliasson, L.J. and Garcia-Duran, P., 2020. The Saga Continues: contestation of EU trade policy. Global Affairs, 6(4-5), pp.433-450. At p.434.

• Enderlein, H., Walti, S. and Zurn, M. eds., 2010. Handbook on multi-level governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

• Esra, U.Y.A.R., Franchino, F. and Arisoy, I.A., The Role of EU Institutions in Common Trade Policy: An Assessment on EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement. International Review of Economics and Management, 7(2), pp.83-104. At p.86-87.

• Fasone, C. and Romaniello, M., 2021. A Temporary Recalibration of Executive–Legislative Relations on EU Trade Agreements? The Case of National and Regional Parliaments on CETA and TTIP. p.183.

• Ficarra, G.M. and Millemaci, E., 2024. CETA, an ex post analysis. At p.3.

• Follesdal, A. and Hix, S. (2006) ‘Why There Is a Democratic Deficit in the EU: A Response to Majone and Moravcsik’. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 533–62.

• Frennhoff Larsén, M., 2020. Parliamentary influence ten years after Lisbon: EU trade negotiations with Japan. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(6), pp.1540-1557.

• Freudlsperger, C., 2020. Trade policy in multilevel government: Organizing openness. Oxford University Press.

• Garcia, M. (2013). From idealism to realism? EU preferential trade agreement policy. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 9(4).

• Geiger, C., 2020. Regulatory and policy issues arising from intellectual property and Investor-State Dispute Settlement in the EU: a closer look at the TTIP and CETA. Research Handbook on Intellectual Property and Investment Law”, Cheltenham (UK)/Northampton, MA (USA), Edward Elgar Publishing, pp.505-527. At p. 526.

• Gheyle, N., 2019. Conceptualizing the parliamentarization and politicization of European policies. Politics and governance, 7(3), pp.227-236.

• Glinski, C., 2023. Market freedoms and 'democratically sound' re-embedding of markets?: The example of CETA. In Economic Constitutionalism in a Turbulent World (pp. 250-281). Edward Elgar Publishing. At p.271.

• Gora, A. and de Wilde, P., 2022. The essence of democratic backsliding in the European Union: deliberation and rule of law. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(3), pp.342-362. At p.344.

• Guimarães, M.H., 2022. EU FTAs and divided sovereignty: transformative shifts in trade authority.

• Hall, P.A., 1986. Governing the economy: The politics of state intervention in Britain and France. New York: Oxford University Press.

• Helboe Pedersen, H. (2013). Is measuring interest group influence a mission impossible? The case of interest group influence in the Danish parliament. Interest Groups & Advocacy, 2(1), 27-47.

• Heliskoski, J., 2021. Mixed agreements as a technique for organizing the international relations of the European Community and its member states. Brill.

• Hix, S., 1998. The study of the European Union II: the ‘new governance’ agenda and its rival. Journal of European public policy, 5(1), pp.38-65. At p.54.

• Hoeglinger, D., 2016. The politicisation of European integration in domestic election campaigns. West European Politics, 39(1), pp.44-63.

• Holden, B., 1988. Understanding liberal democracy. Philip Allan.

• Hooghe, L. and Marks, G., 2001. Multi-level governance and European integration. Rowman & Littlefield.

• Hooghe, L. and Marks, G., 2012. Politicization. The Oxford Handbook of the European Union. At p. 1026.

• Hooghe, L. ed., 1996. Cohesion policy and European integration: building multi-level governance. OUP Oxford. At p.18.

• Hübner, K., Deman, A.S. and Balik, T., 2017. EU and trade policy-making: the contentious case of CETA. Journal of European Integration, 39(7), p. 852.

• Hurrelmann, A. and Wendler, F., 2023. How does politicisation affect the ratification of mixed EU trade agreements? The case of CETA. Journal of European Public Policy, pp.1-25.

• Hurrelmann, A., 2014. Democracy beyond the state: Insights from the European Union. Political Science Quarterly, 129(1), pp.87-105.

• Jarman, H., 2008. The other side of the coin: Knowledge, NGOs and EU trade policy. Politics, 28(1), p.27.

• Jensen, T., 2009. The Democratic Deficit of the European Union. Living Reviews in Democracy, 1.

• Jordan, A., 2001. The European Union: an evolving system of multi-level governance… or government? Policy & Politics, 29(2), pp.193-208.

• Jørgensen, K.E., 2015. The study of European foreign policy: trends and advances. The Sage handbook of European foreign policy, 1, pp.14-30.

• Karlas, J., 2012. National parliamentary control of EU affairs: Institutional design after enlargement. West European Politics, 35(5), pp.1095-1113. At p.1096.

• Karpen, U., 2012. Comparative law: perspectives of legislation. Legisprudence, 6(2), pp.149-189. At p.184.

• Kato, J., 1996. institutions and rationality in politics–three varieties of neo-institutionalists. British Journal of Political Science, 26(4), pp.553-582.

• Kiiver, P., 2006. The national parliaments in the European Union: a critical view on EU constitution-building. At p.71.

• Kleimann, D. and Kübek, G., 2018. The signing, provisional application, and conclusion of trade and investment agreements in the EU: the case of CETA and Opinion 2/15. Legal issues of economic integration, 45(1).

• Kleine, M., Arregui, J. and Thomson, R., 2022. The impact of national democratic representation on decision-making in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(1), pp.1-11. At p.2.

• Knutelská, V., 2011. National parliaments as new actors in the decision-making process at the European level. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 7(3), pp.327-344. At p.330.

• Kohler-Koch, B. and Rittberger, B., 2006. The governance turn in EU studies. J. Common Mkt. Stud., 44, p.27.

• Kuligowski, R., 2021. The Principle of Multi-Level Governance as an Instrument of Democratization of Decision-Making in the European Union. Teka Komisji Prawniczej PAN Oddział w Lublinie, 14(2), pp.307-316. At p.313.

• Langan, M., 2020. A New Scramble for EurAfrica? Challenges for European Development Finance and Trade Policy in the Event of Brexit. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 16(2).

• Lavenex, S. and Schimmelfennig, F., 2013. EU rules beyond EU borders: theorizing external governance in European politics. In EU External Governance (pp. 1-22). Routledge. At p.1.

• Leblond, P. and Viju-Miljusevic, C., 2019. EU trade policy in the twenty-first century: change, continuity and challenges. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(12), pp.1836-1846.

• Lequesne, C., 1996. La Commission européenne entre autonomie et dépendance. Revue française de science politique, pp.389-408.At p.407.

• Levrat, N., Kaspiarovich, Y., Kaddous, C. and Wessel, R.A. eds., 2022. The EU and its Member States’ Joint Participation in International Agreements. Bloomsbury Publishing.

• Lieberson, S., 1987. Making it count: The improvement of social research and theory. Univ of California Press.

• Lord, C. and Pollak, J., 2010. The EU’s many representative modes: Colliding.

• Lupo, N., 2013. National and Regional Parliaments in the EU decision-making process, after the Treaty of Lisbon and the Euro-crisis. Perspectives on Federalism, 5(2).

• Mair, P., 2007. Political Opposition and the European Union1. Government and opposition, 42(1), pp.1-17.

• Maresceau, M., 2010. A typology of mixed bilateral agreements. In Mixed agreements revisited: the EU and its member states in the world (pp. 11-29). Hart Publishing. At p.12.

• Marks, G. and Hooghe, L., 2004. Contrasting visions of multi-level governance. Multi-level governance, pp.15-30.

• Marks, G. and Steenbergen, M., 2002. Understanding political contestation in the European Union. Comparative political studies, 35(8), pp.879-892. At p.881.

• Marks, G., 1992. Structural policy in the European Community.

• Marks, G., 1993. Structural policy and multilevel governance in the EC. The state of the European Community, 2, pp.391-410. At p.407.

• Marks, G., Hooghe, L. and Blank, K., 1996. European integration from the 1980s: State‐centric v. multi‐level governance. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 34(3), pp.341-378.

• Marks, G., Nielsen, F., Ray, L. and Salk, J.E., 1996. Competencies, cracks, and conflicts: regional mobilization in the European Union. Comparative political studies, 29(2), pp.164-192.

• Marx, A. and Van der Loo, G., 2021. Transparency in EU trade policy: A comprehensive assessment of current achievements. Politics and Governance, 9(1), pp.261-271.

• Maurer, A. and Wessels, W., 2001. National parliaments on their ways to Europe. Losers or latecomers? (p. 521). Nomos Verlag.

• McLachlan, C., 2019. Five Conceptions of the Function of Foreign Relations Law. The Oxford handbook of comparative foreign relations law. Oxford Handbooks. At p.30.

• Meunier, S. and Nicolaïdis, K., 2005. The European Union as a trade power. International relations and the European Union, 12, pp.247-269. At p.247.

• Meunier, S. and Nicolaidis, K., 2019. The geopoliticization of European trade and investment policy. J. Common Mkt. Stud., 57, p.103.

• Meunier, S., 2003. Trade policy and political legitimacy in the European Union. Comparative European Politics, 1, pp.67-90. At p.73.

• Moravcsik, A., 2008. The myth of Europe's' democratic deficit'. Intereconomics, 43(6), pp.331-340. At p.332.

• Moravcsik, A., 2020. Liberal intergovernmentalism. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.

• Morgenthau, H., & Nations, P. A. (1948). The struggle for power and peace. Nova York, Alfred Kopf. P..25.

• Nicolaïdis, K., 2013. European Demoicracy and Its Crisis. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 51(2), pp.351-369. At p.353.

• Niemann, A. (2013). EU external trade and the treaty of lisbon: a revised neofunctionalist approach. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 9(4).

• North, D.C., 1990. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge university press.

• O’Brennan, J. and Raunio, T., 2007. Introduction: deparliamentarization and European integration. In National parliaments within the enlarged European Union (pp. 17-42). Routledge.

• Orbie, J. and Khorana, S., 2015. Normative versus market power Europe? The EU-India trade agreement. Asia Europe Journal, 13, pp.253-264.

• Ouellet, R. and Beaumier, G., 2016. L’activité du Québec en matière de commerce international: de l’énonciation de la doctrine Gérin-Lajoie à la négociation de l’AECG. Revue québécoise de droit international/Quebec Journal of International.

• Pagoulatos, G. and Tsoukalis, L., 2012. Multilevel governance. The Oxford Handbook of the European Union. At p.109.

• Pahre, R., 1997. Endogenous domestic institutions in two-level games and parliamentary oversight of the European Union. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(1), pp.147-174.

• Panara, C., 2016. Multi-Level Governance as a Constitutional Principle. The Sub-national Dimension of the EU, Springer International Publishing. At p.18-19.

• Paquin, S., 2006. Les relations internationales du Québec depuis la doctrine Gérin-Lajoie (1965-2005): le prolongement externe des compétences internes. Presses Université Laval.

• Paquin, S., 2018. Multilevel governance and international trade negotiations: The case of Canada’s trade agreements. Borders and margins: Federalism, devolution and multi-level governance, pp.153-166. At p.163.

• Paquin, S., 2022. Trade paradiplomacy and the politics of international Economic Law: The inclusion of Quebec and the exclusion of Wallonia in the CETA negotiations. New political economy, 27(4), pp.597-609.

• Pereira Coutinho, F., 2022. The Legal Nature of New Generation Free Trade Agreements: Lessons from the CETA Saga. The Legal Nature of New Generation Free Trade Agreements: Lessons from the CETA Saga”, Perspectivas–Journal of Political Science, 27(2022), pp.77-92. At p.78.

• Pernice, I., 2001. The role of national parliaments in the European Union. Walter Hallstein Institut, WHI-Paper, 5(01).

• Pierre, J. and Peters, B.G., 2020. Governance, politics and the state. Bloomsbury Publishing.

• Pierre, J. ed., 2000. Debating governance: Authority, steering, and democracy. OUP Oxford. At p.3.

• Pitkin, H., 1964. Hobbes's Concept of Representation—I. American Political Science Review, 58(2), pp.328-340. At p.329.

• Puccio, L. and Conconi, P., 2021. EU trade agreements: To mix or not to mix, that is the question. Journal of World Trade, 55(2).

• Quick, R. and Gerhäuser, A., 2019. The Ratification of CETA and other Trade Policy Challenges After Opinion 2/15. ZEuS Zeitschrift für Europarechtliche Studien, 22(4), pp.505-528.

• Randour, F., 2021. Studying the influence of national parliaments in EU affairs: reconnecting empirical research and the Principal-Agent approach. Political Research Exchange, 3(1), p.1989314.

• Rauh, C., 2015. Communicating supranational governance? The salience of EU affairs in the German Bundestag, 1991–2013. European Union Politics, 16(1), pp.116-138.

• Raunio, T., 2009. National parliaments and European integration: What we know and agenda for future research. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 15(4), pp.317-334.

• Riffel, C., 2019. The CETA opinion of the European Court of Justice and its implications—not that selfish after all. Journal of International Economic Law, 22(3), pp.503-521.

• Risse, T., 2007. Social constructivism meets globalization. Globalization theory: Approaches and controversies, 4, p.126.

• Rixen, T. and Zangl, B., 2013. The politicization of international economic institutions in US public debates. The Review of International Organizations, 8, pp.363-387.

• Roederer-Rynning, C. and Kallestrup, M., 2020. National parliaments and the new contentiousness of trade. In The EU and the New Trade Bilateralism, pp. 47-61. Routledge. At p. 60.

• Rosas, A., 1998. Mixed Union–Mixed Agreements. International law aspects of the European Union, 145.

• Schakel, A.H., 2020. Multi-level governance in a ‘Europe with the regions. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22(4), pp.767-775. At p.768.

• Scharpf, F.W., 1998. Interdependence and democratic legitimation (Vol. 98, No. 2). Köln: Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung.

• Scharpf, F.W., 2009. Legitimacy in the multilevel European polity. European political science review, 1(2), pp.173-204.

• Schmidt, V.A., 2013. Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: Input, output and ‘throughput’. Political studies, 61(1), pp.2-22.

• Schmitter, P.C. and Karl, T.L., 1991. What democracy is... and is not. Journal of democracy, 2(3), pp.75-88.

• Scott, C., 2002. The governance of the European Union: The potential for multi‐level control. European Law Journal, 8(1), pp.59-79. At p.69.

• Shapiro, I., 2003. John Locke’s democratic theory. na.

• Shepsle, K.A., 1986. The positive theory of legislative institutions: an enrichment of social choice and spatial models. Public Choice, pp.135-178.

• Shklar, J.N., 1987. Political theory and the rule of law.

• Smith, M., 2007. The European Union and international order: European and global dimensions. European Foreign Affairs Review, 12(4).

• Sternberg, C., 2013. The Struggle for EU Legitimacy: Public Contestation, 1950-2005. Springer. At p.187.

• Stetter, S., 2013. The EU as a structured power: Organizing EU foreign affairs within the institutional environment of world politics. Journal of International Organizations Studies, 4(2), pp.54-71. At p.56.

• Strøm, K. and Müller, W.C., 1999. Political parties and hard choices. Policy, office, or votes, pp.1-35.

• Van der Loo, G. and Hahn, M., 2020. EU Trade and Investment Policy since the Treaty of Lisbon. Centre for European Policy Studies, October, 11. At p.11.

• Van der Loo, G., 2018. Less is more? The role of national parliaments in the conclusion of mixed (trade) agreements. The Role of National Parliaments in the Conclusion of Mixed (Trade) Agreements (January 2018). TMC Asser Institute for International & European Law, 1.

• Van Gruisen, P., Vangerven, P. and Crombez, C., 2019. Voting behavior in the Council of the European Union: The effect of the trio presidency. Political Science Research and Methods, 7(3), pp.489-504.

• Van Hecke, S. and Wolfs, W., 2015. The European parliament and European foreign policy. The SAGE handbook of European foreign policy, pp.291-305.

• Verdier, P.H. and Versteeg, M., 2018. Separation of Powers, Treaty-Making, and Treaty Withdrawal: A Global Survey. The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Foreign Relations Law. Oxford Handbooks. At p.142.

• Wagner, W., 2015. National parliaments. The SAGE handbook of European foreign policy, pp.359-371. At p.370.

• Waibel, M., 2013. Competence Review: Trade and Investment. Available at SSRN 2507138.

• Waltz, K. N. (2001). Man, the state, and war: A theoretical analysis. Columbia University Press.

• Ware, A., 1992. Liberal democracy: one form or many?. Political Studies, 40(1_suppl), p.137.

• Weber, M., 2019. Power, domination, and legitimacy. In Power in modern societies (pp. 37-47). Routledge.

• Weingast, B.R., 1996. Political institutions: Rational choice perspectives. A new handbook of political science, 167, p.168.

• Weiß, W., 2022. Implementing CETA in the EU: Challenges for democracy and executive–legislative balance. In CETA Implementation and Implications: Unravelling the puzzle (pp. 42-69). McGill-Queens University Press.

• Wendler, F. and Hurrelmann, A., 2022. Discursive postfunctionalism: theorizing the interface between EU politicization and policy-making. Journal of European Integration, 44(7), pp.941-959.

• Wendler, F., 2014. Debating Europe in national parliaments: Justification and political polarization in debates on the EU in Austria, France, Germany and the United Kingdom. OPAL Online Paper, 17, p.2014.

• Wessel, R.A. and Van der Loo, G., 2017. The non-ratification of mixed agreements: Legal consequences and solutions. Common Market Law Review, 54(3).

• Winzen, T., 2013. European integration and national parliamentary oversight institutions. European Union Politics, 14(2), pp.297-323.

• Woolcock, S., 2010. EU trade and investment policymaking after the Lisbon treaty. Intereconomics, 45(1), pp.22-25.

• Wouters, J. and Raube, K., 2018. Rebels with a cause? Parliaments and EU trade policy after the Treaty of Lisbon. In The democratisation of EU international relations through EU law (pp. 193-209). Routledge.

• Yencken, E., 2016. Lessons from CETA: Its implications for future EU Free Trade Agreements. Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

• Young, A. R. (2017). The new politics of trade: Lessons from TTIP. New York, NY: Agenda Publishing.

• Zapata-Barrero, R., Caponio, T. and Scholten, P., 2017. Theorizing the ‘local turn’in a multi-level governance framework of analysis: A case study in immigrant policies. International Review of administrative sciences, 83(2), pp.241-246.

Personal Methods-Specific Bibliography (So Far)

• Bryman, A., 2016. Social research methods. Oxford university press

• Caramani, D. 2017. Comparative politics. Oxford University Press.

• Chynoweth, P., 2008. Legal research. Advanced research methods in the built environment, 1. At p.29.

• Collier, D., 1991. The comparative method: Two decades of change. Comparative Political Dynamics: Global Research Perspectives, HarperCollins Publishers.

• De Dios, M.S., 2014, June. Different comparative approaches in the study of parliaments. In First Annual Conference of the ERASMUS Academic Network on Parliamentary Democracy in Europe (PADEMIA), Brussels(pp. 12-13).

• Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S. eds., 2011. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. sage.

• Edwards, R. and Holland, J., 2013. What is qualitative interviewing? (p. 128). Bloomsbury Academic.

• Gawas, V.M., 2017. Doctrinal legal research method a guiding principle in reforming the law and legal system towards the research development.

• Gerring, J., 2017. Qualitative methods. Annual review of political science, 20(1), pp.15-36.Ginsburg, T. The Oxford handbook of comparative foreign relations law. Oxford Handbooks.

• Hall, M.A. and Wright, R.F., 2008. Systematic content analysis of judicial opinions. Calif. L. Rev., 96, p.63.

• Harris, B., 2015. Constitutional law guidebook. Oxford: Oxford University Press. At p.3.

• Hervey, T., Cryer, R., Sokhi-Bulley, B. and Bohm, A., 2011. Research methodologies in EU and international law. Bloomsbury Publishing. At p.28.

• Hofmann, H.C., 2020. Research Frameworks in Comparative Public Law: Law as Category, as Source and as Variable. University of Luxembourg Law Working Paper, (2020-013).

• Hutchinson, T. and Duncan, N., 2012. Defining and describing what we do: doctrinal legal research. Deakin law review, 17(1), pp.83-119.

• Karpen, U., 2012. Comparative law: perspectives of legislation. Legisprudence, 6(2), pp.149-189. At p.153.

• Krippendorff, K., 1980. Validity in content analysis.

• Landman, T., 2002. Issues and methods in comparative politics: an introduction. Routledge. At p.25.

• Leavy, P. ed., 2014. The Oxford handbook of qualitative research. Oxford University Press, USA.

• Lijphart, A., 1971. Comparative politics and the comparative method. American political science review, 65(3), pp.682-693.

• Lijphart, A., 1989. Democratic political systems: Types, cases, causes, and consequences. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 1(1), pp.33-48

• Linos, K., 2015. How to Select and Develop International Law Case Studies: Lessons from Comparative Law and Comparative Politics. American Journal of International Law, 109(3), pp.475-485.

• Lock, I. and Seele, P., 2018. Gauging the rigor of qualitative case studies in comparative lobbying research. A framework and guideline for research and analysis. Journal of Public Affairs, 18(4), p.e1832.

• Lodge, M., 2013. Semistructured interviews and informal institutions: Getting inside executive government. In Political science research methods in action (pp. 181-202). London: Palgrave Macmillan U

• Longhurst, R., 2003. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Key methods in geography, 3(2), pp.143-156. p.103.

• Mahoney, J., 2007. Qualitative methodology and comparative politics. Comparative political studies, 40(2), pp.122-144.

• Manheim, J.B., Rich, R.C., Willnat, L. and Brians, C.L., 2012. Empirical political analysis. Pearson Education UK.

• Mark Van Hoecke, ‘Legal Doctrine: Which Method(s) for What Kind of Discipline?’ in Mark Van Hoecke (ed), Methodologies of legal research: Which Kind of Method for What Kind of Discipline? (Hart 2011) 11.

• Marx, A., Rihoux, B. and Ragin, C., 2014. The origins, development, and application of Qualitative Comparative Analysis: the first 25 years. European Political Science Review, 6(1), pp.115-142.

• McLachlan, C., 2019. Five Conceptions of the Function of Foreign Relations Law. The Oxford handbook of comparative foreign relations law. Oxford Handbooks. At p.33.

• Ostrom, E., 1991. Rational choice theory and institutional analysis: Toward complementarity. American political science review, 85(1), pp.237-243.

• Randour, F., 2021. Studying the influence of national parliaments in EU affairs: reconnecting empirical research and the Principal-Agent approach. Political Research Exchange, 3(1), p.1989314.

• Ropret, M., Aristovnik, A. and Kovač, P., 2018. A Content analysis of the rule of law within public governance models: old vs. new EU member states. NISPAcee Journal of Public Administration and Policy, 11(2), pp.129-152. At p.138.

• Salehijam, M., 2018. The value of systematic content analysis in legal research. Tilburg Law Review, 23(1-2), pp.34-42.

• Sartori, G., 1970. Concept misformation in comparative politics. American political science review, 64(4), pp.1033-1053.

• Smelser, N.J., 2013. Comparative methods in the social sciences. Quid Pro Books.

• Steinmo, S., Thelen, K. and Longstreth, F. eds., 1992. Structuring politics: historical institutionalism in comparative analysis. Cambridge University Press.

• Tsui, J. and Lucas, B., 2013. Methodologies for measuring influence. GSDRC Applied Knowledge Services prepared for DFID. UK, London.

• VanGestel, R. and Micklitz, H.W., 2011. Revitalizing Doctrinal Legal Research in Europe: What About Methodology?

• Vranken, J.B., 2010. Methodology of legal doctrinal research. In Methodologies of legal

• Zweigert, K. and Koetz, H., 1987. An Introduction to Comparative Law. Vol. II. 2d ed. Translated by T. Weir.

Selected Case Studies

Key Findings (So Far)

1. Methodology: This research will examine the trade policymaking processes of the EU and Canada during the CETA negotiations and ratification, focusing on the roles of member states and provinces. It employs a comparative legal and political science approach to understand the nuances and differences between these entities. Drawing on Zweigert and Kötz's definition, the study views comparative law both as a method of intellectual activity focused on law and comparison, and as a distinct subject with its own methodologies. Ginsburg's approach to comparative constitutional perspective and foreign relations law will guide this analysis, aiming to explore the distribution of power, institutional variations, and the implications of these differences on trade agreement negotiations and implementations. Additionally, the research will incorporate a political comparative analysis, as described by Collier, to address methodological challenges in studying a limited number of cases. This multidisciplinary approach will facilitate a comprehensive examination of the legal frameworks within the EU and its member states, shedding light on their impact on trade agreement processes.

2. Hypothesis: So far, the main areas, which have brought upon this “crisis” of the European trade policy and an involvement, on this matter, of domestic parliaments, are the following: the constitutional and political frameworks in the EU Member States, the democratic deficit of the EU and the mounting parliamentary contestation/politicisation of EU’s trade policy and the differences in the understanding of liberal democracy between and within the member states. These findings allowed to structure my thesis around two main hypotheses related to these areas. The first hypothesis examines whether the influence of domestic parliaments over the European Union is dictated by "hard law," which in this thesis is referred to as legal influence, and by their national legal frameworks, which I have defined as legal reasons. My analysis will include both the national and subnational levels, in the case of federal member states. It will involve comparing the specified requirements of the four selected member states for acting within the EU Trade Policy, as well as analysing the national laws that enable them to influence the ratification or rejection of an EU trade agreement. This hypothesis suggests that the strength of national legal requirements on trade policy significantly influences a domestic parliament's impact on the EU’s trade agreement capabilities. This was identified so far through a literature review. The second hypothesis understanding the extent of the political reasons that make domestic parliaments assert their position in EU trade policy, thus influencing the EU’s ability to conclude trade agreements. The aim is to outline how political factors lead parliamentary bodies to leverage their domestic political influence to act at the EU level. This process can be explained through the lens of rational-choice institutionalism. According to this theory, following a rational-choice assumption that actors seek to maintain and increase their influence in the decision-making process, we can assume that national parliaments should seek influence in European decision-making, and its multi-level nature prompting them to attempt this at multiple levels, including the European level, to succeed in their goals. Based on what is outlined in the state of the art, in this thesis, I argue that the willingness of domestic parliaments to act is emphasized by the presence of parliamentary contestation. In this sense, I argue that parliamentary contestation can be an indication of a higher involvement on domestic parliaments in the EU decision making process, especially in trade policy. As acknowledged by Hurrelmann and Wendler, today, “there is broad agreement in the literature that increased public salience and contestation are key features of the new politics of trade observed in the EU”, and that this increased contestation, regarding the EU within both public opinion and party politics, has the potential to transform the functions of national parliaments.

Social Relevance of your Research

In this context, numerous publications recognize that national parliaments possess scrutiny instruments , yet the question of how they shape EU‐level decisions in practice remains largely underexplored. This thesis attempts to show parliamentary influence by firstly understanding how and why parliamentary action happens through an analysis of national constitutional legal and political perspectives, and then explaining why parliaments intervene under certain conditions, citing rational incentive structures and high contestation. Finally demonstrating what real constraints parliaments place on EU negotiators, thus altering the EU’s. The novelty of this research comes from the fact that parliaments are not treated as merely passive or symbolic actors in EU trade policy, but as important actors, especially under “mixed” treaty procedures. Indeed, this goes against the prevailing view in the literature that states that the Lisbon Treaty was widely seen to strengthen the European Parliament at the expense of national legislatures. More specifically, this thesis challenges the assumption that national parliaments have become irrelevant in external EU policy. In this sense, I argue that high levels of public contestation create domestic electoral incentives for MPs to use ratification prerogatives strategically. More specifically, this thesis argues that domestic parliaments, as rational actors, engage in the EU multi‐level system to maximize electoral or political gains . In this context, the innovation of rational choice institutionalism lies in its emphasis on analysing how institutions impact and influence decisions, specifically in determining which interests or preferences prevail in the policymaking process. By combining MLG and rational choice offers a unified model of how vertical “shifts”, from the EU to the regional level, reflect both legal rule structures and political strategies. Furthermore, by analysing different MS and applying this legal and political comparative approach this thesis attempts to uncover generalizable patterns of parliamentary activism.

Other novel aspect of this thesis is its revisiting of the democratic deficit debates through the lens of domestic parliaments. Indeed, many discussions of the EU’s democratic deficit emphasize the EP or the role of civil society organisations’ consultation. However, the contribution of domestic legislatures to EU legitimacy has been neglected. This thesis will indicate that domestic parliamentary involvement can also bolster “input legitimacy” by offering direct representation of national electorates. Furthermore, based on the work of Brack and Costa, this thesis indicates that democratic accountability is enhanced when parliaments stage public deliberations. This thesis argues for seeing parliamentary involvement not merely as a “procedural obstacle” but as an integral source of democracy. Overall, the main objective of the thesis is to create a framework to explain causation, variation and implication of the involvement of domestic parliaments in EU trade policy. Causation explains how the presence of formal constitutional powers plus political mobilization leads parliaments to influence EU trade agreements’ negotiations and implantation. Variation explains why some parliaments become major players, such as Wallonia, while others remain reticent or do not use their constitutional powers. And finally, implication explains how these parliamentary interventions affect not just CETA, but the broader trajectory of EU trade policy and the EU’s ability to conclude trade agreements.

In sum, the thesis’s central novelty lies in offering an interdisciplinary, comparative study that integrates legal scholarship with rational choice and MLG based insights to understand the role of domestic parliaments in the EU. By systematically documenting these through the CETA case, and comparing across multiple Member States, this thesis aims to fill gaps in the literature of EU trade policy. It advances the literatures on EU external relations law, comparative foreign relations law, the role of domestic parliaments in the EU, and broader discussions about the EU’s legitimacy.

Samir holds an MA in European Affairs from the Institute of European Studies of the ULB and BA in Political Sciences from the ULB. Before starting his PhD journey, Samir worked as financial product developer in Luxembourg.

Currently, he is also a researcher at the Chair on New Challenges of Economic Globalization (ULaval), at the Research Cluster on European Integration and Public Policies (LUISS) and at the Center for the Study of Politics (ULB).

• Philosophy of social science (LUISS University)

• Theory in Political Science I: Democracy and representation (LUISS University)

• Quantitative Methods (LUISS University)

• Research Design in Politics (LUISS University)

• Research Design in Law (LUISS University)

• Legal writing (LUISS University)

• Qualitative Methods (LUISS University)

• Alternative Justice and Pretrial Sentencing (LUISS University)

• Multilevel Regulation in public policy (LUISS University)

• Market and competition (LUISS University)

• Directed readings in Law (Université Laval)

• Directed readings in Political Science (Université Laval)

Seminars

• DiSP Young Resarchers’ Seminar Series (LUISS Univesity)

• Political Science Department’s Seminar Series (LUISS Univesity)

Summar Schools

• Summer Program: Parliamentary Democracy in Europe 12th Edition: “Parliaments in front of the multiple crises: From global to local”, 2023, LUISS, Rome, Italy.

• Gem-Diamond Summer School, 2024. Brussels, Belgium.

• Gem-Diamond Autumn School, 2024, Brussels, Belgium.

Academic conferences

• Presentation at the European in International Affairs Conference (EUIA). 2023. Brussels, Belgium.

• Presentation at the LUISS Graduate's Conference, 2023. Rome, Italy.

• Presentation at the The Governance of Digital Trade: Crossroads of Divergent Approaches. 2023. Foreign Trade Univerity, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Publications (so far)

• El Khanza, Samir (2025). The global governance of digital trade: just another Brussels effect?. In La gouvernance du commerce numérique: regards croisés sur des approches différentes. Presses de l’Université Laval. [forthcoming]

• El Khanza, Samir (2025). From dissensus to change: The Evolution of EU Trade Policy in the Wake of CETA. In Ramona Coman, Frederik Ponjaert & Nicholas Levrat (eds.) Dissensus over liberal democracy: actors, policies, and institutions. Routledge [forthcoming]

• El Khanza, Samir & Radaelli, Claudio (2025). The Policy Impact of Social Sciences. In Ramona Coman, Frederik Ponjaert & David Paternotte (eds.). Impact and Social Sciences: A Conceptual Index. Oxford University Press. [forthcoming]

Memberships

• Chair on New Challenges of Economic Globalization, Université Laval.

• Centre d’Etude de la Vie Politique (Cevipol), Université Libre de Bruxelles.

• Centre interdisciplinaire de recherche sur la gouvernance mondiale (CIRGoM), Université Laval.

• Chair on New Challenges of Economic Globalization, Université Laval.

-

Mario Draghi's Vision for Europe's Future: Is It Enough?

2 July 2025

This Draghi report on "The Future of European Competitiveness” examines the challenges facing the Single Market. What does it contain and bring to mind?

-

Navigating the Ph.D. Journey: A comparison between Italy and Canada From LUISS to Laval

28 March 2024

Starting a Ph.D. journey is an important step, yet the experience can vary depending on the geographic or institutional context of such an academic journey

-

From Academia to Adventure: Unpacking the Hanoi Conference on "The Governance of Digital Trade: crossroads of different approaches."

23 February 2024

Samir El Khanza's journey through Digital Governance and Cultural Discovery

-

Exploring Parliaments in front of the multiple crises

22 November 2023

My Summer School Experience in Rome

-

The 2nd Interdisciplinary Methods Workshop hosted in Copenhagen

27 June 2023

The GEM Fellows have reunited in Copenhagen to attend an Interdisciplinary Methods Workshop, organised by the iCourts at the Faculty of Law in Copenhagen.

-

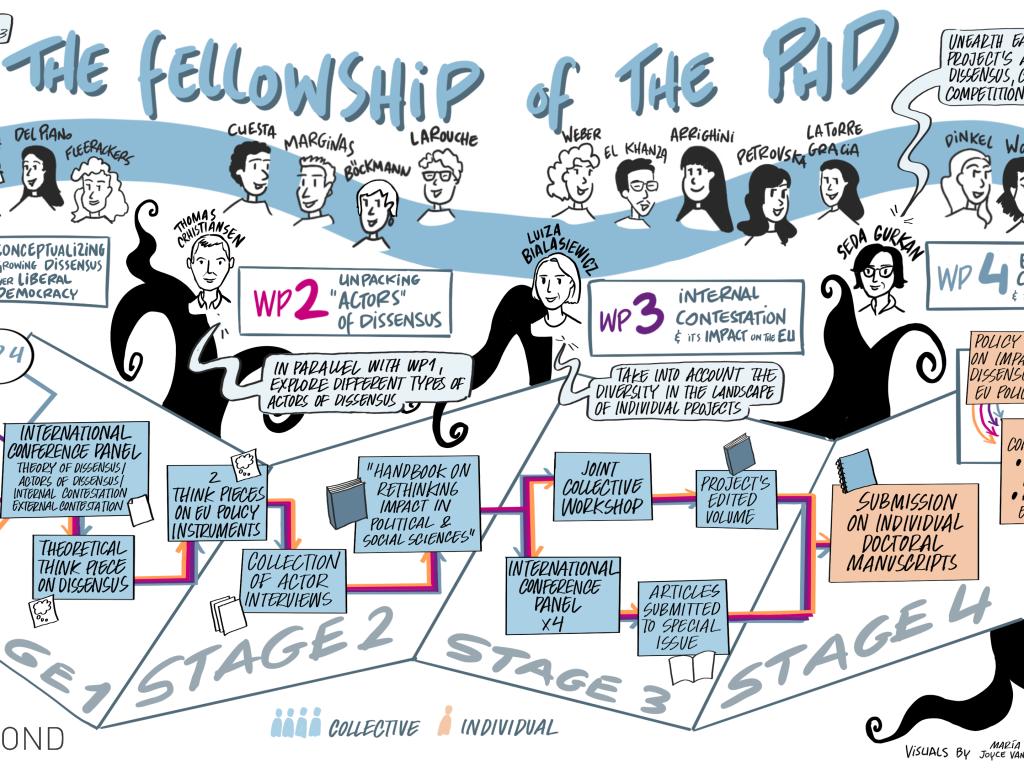

Birth of the GEM-DIAMOND Fellowship of the Ph.D.

1 October 2022

16 MSCA Fellows successfully selected following a gruelling selection process.