Pedro Cuesta García

GEM-DIAMOND doctoral fellow

ESR 5 – National and European courts reacting to dissensus: The case of fundamental rights protection

Pedro is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie PhD candidate at Luiss University in Rome and at iCourts in the University of Copenhagen under the framework of the GEM-DIAMOND and Horizon Europe programmes. His research focuses on the constitutional aspects of EU law, the connections between EU and national law, and the role of courts in shaping the EU polity and the integration process. Open-minded and critical, always open to debate and new ideas.

National Constitutional Courts and the Limits of Judicial Cooperation in the EU

Supervisors

- Giovanni Piccirilli

- Mikael Madsen

Research abstract

This study’s value lies in its interdisciplinary approach, integrating constitutional law, judicial politics, and legal theory to provide a deeper understanding of multilevel governance and court interactions in the EU legal order. By critically engaging with recent developments in constitutional pluralism, the rule of law crisis, and the strategic use of constitutional identity by national courts, the dissertation offers insights into the evolving judicial landscape of the European Union.

Research Question(s)

(2) How has academic literature described, explained, and normatively evaluated the interaction between national apex courts and the Court of Justice of the European Union? To what extent do existing theoretical accounts offer a comprehensive and normatively robust understanding of these judicial conflicts?

(3) What are the underlying justifications for the constitutional limits that national apex courts impose on EU law? What constitutional imaginaries or narratives do these courts invoke to assert the primacy of national constitutional orders, and how coherent or defensible are these justifications from both theoretical and practical perspectives?

(4) Can national constitutional identity claims be strategically or abusively invoked? If so, how can one distinguish between good-faith and abusive claims? Is there a benchmark for doing so, and can the values of Article 2 TEU serve as a reliable standard in this context?

Research Hypothesis(es)

Personal Research Bibliography (So Far)

- Donoso Cortés, J. (1954). Obras. Madrid, Spain: Imprenta Tejado, at 200.

- Schmitt, C. (1992). Political Theology: Four chapters on the concept of sovereignty. Chicago, US: Chicago University Press.

- MacCormick, N. (1993). Beyond the Sovereign State. The Modern Law Review, 56, 1-18.

- Pernice, I. (1999). Multilevel Constitutionalism and the Treaty of Amsterdam: European Constitution-Making Revisited? Common Market Law Review, 36 (4), 703-750.

- Kumm, M. (1999). Who is the Final Arbiter of Constitutionality in Europe? Three Conceptions of the Relationship between the German Federal Constitutional Court and the European Court of Justice. Common Market Law Review, 36, 351.

- Walker, N. (2002), The Idea of Constitutional Pluralism. The Modern Law Review, 65, 317-359.

- Maduro, M. (2003). “Contrapunctual Law: Europe’s Constitutional Pluralism in Action” in N. Walker (ed.), Sovereignty in Transition. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- Eijsbouts, W. T. (2010). Wir Sind das Volk: Notes About the Notion of ‘The People’ as Occasioned by the Lissabon-Urteil. European Constitutional Law Review, 6(2), 199–222.

- Mayer, F., & Wendel, M. (2012). “Multilevel Constitutionalism and Constitutional Pluralism Querelle Allemande or Querelle d’ Allemande?” in Avbelj, M., and Komárek, J. (eds.), Constitutional Pluralism in the European Union and Beyond. Oxford: Hart.

- Marti, G. (2013). Construcción política de la Unión Europea y poder constituyente. Teoría y Realidad Constitucional, (32), 309–322.

- Wendel, M. (2013). Comparative reasoning and the making of a common constitutional law: EU-related decisions of national constitutional courts in a transnational perspective. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 11(4), 981–1002.

- Klemen, J. (2014). Constitutional Pluralism in the EU. Oxford Studies in European Law, Oxford.

- Fabbrini, F. (2015). After the OMT Case: The Supremacy of EU Law as the Guarantee of the Equality of the Member States. German Law Journal, 16(4), 1003-1023.

- Baquero Cruz, J. (2016) Another Look at Constitutional Pluralism in the European Union. European Law Journal, 22, 356–374.

- Cheneval, F., & Nicolaidis, K. (2017). The social construction of demoicracy in the European Union. European Journal of Political Theory, 16(2), 235-260.

- Kelemen, R. D., & Pech, L. (2018). Why autocrats love constitutional identity and constitutional pluralism: Lessons from Hungary and Poland. Reconnect Working Paper No. 2.

- Albert, R. (2019). Constitutional Amendments: Making, Breaking, and Changing Constitutions. New York, Oxford Academic.

- Lawrance, J. C. (2019). Constitutional Pluralism’s Unspoken Normative Core. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 21, 24–40.

- Bobić, A. (2020). Constructive Versus Destructive Conflict: Taking Stock of the Recent Constitutional Jurisprudence in the EU. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies. 2020, 22:60-84

- Colón-Ríos, J. (2020). The Constituent Power and the Law. Oxford, UK: Oxford academic.

- Schutze. R. (2020). Models of demoicracy: some preliminary thoughts. EUI Working Papers LAW, 2020/08.

- Patberg, M. (2021). Constituent Power in the European Union. Oxford, Oxford Academic.

- Coman, R., & Brack, N. (2023). Understanding Dissensus over Liberal Democracy in the Age of Crises: Theoretical Reflections. In R. Coman & N. Brack (Eds.), Dissensus Over Liberal Democracy. Working Paper Series N°1, RED SPINEL Project.

- Scarcello, O. (2023). Radical Constitutional Pluralism in Europe. Routledge.

- Scholtes, J. (2023). The Abuse of Constitutional Identity in the European Union. Oxford, Oxford Academic.

Personal Methods-Specific Bibliography (So Far)

- Raz, J. (1977). The Rule of Law and its Virtue. Law Quarterly Review, 93, 195.

- Stone Sweet, A. (2000). Governing with Judges. Constitutional Politics in Europe. New York: Oxford University Press.

- McGuire, K. T., & Stimson, J. A. (2004). The least dangerous branch revisited: New evidence on Supreme Court responsiveness to public preferences. Journal of Politics, 66(4), 1018–1035.

- Tamanaha, B. (2004). On the Rule of Law: History, Politics, Theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Tamanaha, B. (2006). Law as a Means to an End: Threat to the Rule of Law. Cambridge University Press.

- Epstein, L. & Andrew D. M. (2010). Does Public Opinion Influence the Supreme Court? Possibly Yes (But We’re Not Sure Why). University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law 13: 263-281 (Symposium).

- Casillas, C. J., Enns, P. K., & Wohlfarth, P. C. (2011). How Public Opinion Constrains the U.S. Supreme Court. American Journal of Political Science, 55(1), 74–88.

- Conway, G. (2012). The Limits of Legal Reasoning and the European Court of Justice. Cambridge Studies in European Law and Policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Beck, G. (2013). The Legal Reasoning of the Court of Justice of the EU. Hart: Oxford.

- Muir, E., Dawson, M., & de Witte, B., (2013). “Introduction: the European Court of Justice as a political actor”. In Dawson, M., de Witte, B., & Muir, E. (editor/s): Judicial activism at the European Court of Justice: causes, responses and solutions. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Bobek, M. (2014). Legal Reasoning of the Court of Justice of the EU. European Law Review, 39(3), 418-428.

- Dawson, M. (2014). How Does the European Court of Justice Reason? European Law Journal 20 (3), 423–435.

- Carrubba, C. J., & Matthew J. G. (2015). International Courts and the Performance of International Agreements. A General Theory with Evidence from the European Union. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Larsson, O., & Naurin, D. (2016). Judicial Independence and Political Uncertainty: How the Risk of Override Impacts on the Court of Justice of the EU. International Organization, 70(1), 377–408.

- Blauberger, M., & Schmidt, S. K. (2017). The European Court of Justice and its political impact. West European Politics, 40(4), 907-918.

- Loughlin, M. (2017). Political Jurisprudence. Oxford University Press.

- Saurugger, S., & Terpan, F. (2017). The Court of Justice of the European Union and the Politics of Law. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Blauberger, M., Heindlmaier, A., Kramer, D., Martinsen, D. S., Thierry, J. S, Schenk, A., & Werner, B. (2018). ECJ Judges read the morning papers. Explaining the turnaround of European citizenship jurisprudence. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(10), 1422-1441.

- Van Malleghem, P. A., (2018). “Reflections on European Legal Formalism”. In Perišin, T. and Rodin, S. (editors): The Transformation or Reconstitution of Europe. 1st edn. Hart Publishing.

- Blauberger, M. & Martinsen, D. S. (2020) The Court of Justice in times of politicisation: ‘law as a mask and shield’ revisited. Journal of European Public Policy, 27:3, 382-399.

- Mańko, R. (2020). Methods of Legal Interpretation, Legitimacy of Judicial Discretion and Decision-Making in the Field of the Political: a theoretical model and case study. International Comparative Jurisprudence, 6(2), 108-117.

- Bartl, M., and Lawrence, JC., (eds). (2022). The Politics of European Legal Research: Behind the Method. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Madsen, M. R., Nicola, F., & Vauchez, A. (eds). (2022). Researching the European Court of Justice: Methodological Shifts and Law’s Embeddedness. Cambridge University Press.,

- Moser, C., & Rittberger, B. (2022). The CJEU and EU (de-)constitutionalization: Unpacking jurisprudential responses. International Journal of Constitutional Law, Volume 20, Issue 3, 1038–1070.

- Dothan, S., Mair, S., & Mayoral, J.A (2024). Introduction: Making the invisible visible in European Union law. European Law Open; 3(2), 360-371.

- van den Brink M. (2024). Political, not (just) legal judgement: studying EU institutional balance. European Law Open; 3(2), 389-401.

Selected Case Studies

Germany and Italy represent long-standing, jurisprudentially rich traditions in the constitutional dialogue with the CJEU. The German Federal Constitutional Court has played a central role in shaping the boundaries of constitutional pluralism, developing sophisticated doctrines such as ultra vires review and national constitutional identity in cases like Solange, Maastricht, Lisbon, and Weiss. Italy, through the controlimiti doctrine, offers a more dialogical approach, as exemplified in the Taricco saga, balancing loyalty to EU law with a strong defence of national constitutional principles.

Denmark provides a distinctive model of judicial resistance through the Ajos judgment of the Danish Supreme Court. Unlike Germany or Italy, the Danish court’s approach is more statutory and sovereignty-based, highlighting concerns around democratic delegation and legal certainty. As a small Member State with a strong legal tradition, Denmark’s stance offers a valuable comparative contrast. Spain, while less frequently examined in this context, has developed a significant body of jurisprudence addressing the constitutional limits of EU law, especially regarding treaty ratification and the articulation of national constitutional identity. Spain’s case illustrates how even traditionally integrationist legal cultures may assert foundational constitutional boundaries.

Crucially, this selection deliberately excludes Member States currently experiencing systemic rule of law deterioration or where constitutional courts are widely perceived to act in bad faith or under political influence. The aim is to assess whether good-faith constitutional resistance—advanced by courts operating within functioning liberal democracies—can be justified both in practice and in theory. This choice allows the dissertation to interrogate the legitimacy and coherence of such resistance without conflating principled judicial dissent with illiberal or abusive legal strategies.

Taken together, these four case studies offer a diverse yet coherent sample, encompassing different legal traditions, judicial cultures, times of accession to the EU, and constitutional narratives. They enable a nuanced exploration of how national courts engage with the authority of EU law while navigating—and, in some cases, reinforcing—the shared values and commitments of the Union’s constitutional order.

Key Findings (So Far)

1. Judicial Conflicts as a Symptom of Deeper Legitimacy Issues:

First, the conflicts between national apex courts and the CJEU reflect not only doctrinal disagreement but a deeper tension concerning constitutional legitimacy and authority. At the core of this tension lies the theory of constituent power, invoked by national courts to justify their constitutional supremacy. These courts claim that their legal orders derive legitimacy from a foundational act of democratic self-determination—something the EU, lacking a constituent moment, cannot match. This makes constituent power the final battleground in disputes over the limits of EU legal authority.

2. Limits of Constitutional Pluralism:

Second, constitutional pluralism, while once a dominant theory for understanding EU–national court relations, has shown itself vulnerable to abuse. Its openness to multiple sources of constitutional authority risks legitimising illiberal claims. In response, a second generation of pluralists has sought to reform the theory by grounding it in substantive normative principles. However, this evolution faces its own challenges, namely the lack of a common understanding of what the content of the fundamental values of the EU is and who should define it.

3. Article 2 TEU as a Normative Benchmark:

Third, I argue that the values of Article 2 TEU—if operationalised carefully—can serve as a normative benchmark to distinguish between constructive and destructive constitutional resistance. This involves recognising violations of these values without imposing a rigid constitutional blueprint that would threaten pluralism itself. This process of “operationalizing” Article 2 means defining its values through negative dialectics (i.e., identifying what violates them), without prescribing what is the content of the values.

4. A Typology of Conflicts and National Strategies

Finally, through my comparative case studies (Germany, Italy, Denmark, Spain), I show that national courts adopt different strategies and narratives, ranging from dialogical engagement to open defiance. Not all conflict is harmful: when grounded in shared values and conducted in good faith, judicial dissensus may play a constructive role in shaping the EU’s constitutional order.

Social Relevance of your Research

By offering a normative and theoretical framework—grounded in the values of Article 2 TEU—to distinguish between constructive and destructive forms of judicial dissensus, this dissertation provides tools to protect the integrity of the EU legal order while respecting national constitutional diversity and democratic legitimacy. Its findings are directly relevant to policymakers, legal practitioners, and institutions committed to defending democracy, judicial independence, and the rule of law across Europe.

Moreover, the study investigates the constitutional narratives invoked by national constitutional and supreme courts to justify limits on the authority of the EU legal order. These narratives illuminate deeper questions about democratic legitimacy, constitutional foundations, and the role of constituent power in shaping legal systems. Ultimately, this research contributes to the broader societal goal of preserving democratic legitimacy, legal certainty, and the coherence of European integration in an era of constitutional turbulence.

Pedro holds a Bachelors of Laws (LLB) from the University Carlos III de Madrid, and a "European Public Law & Governance" Masters of Laws (LLM) from the European Law School of Maastricht University. Prior to joining the GEM-DIAMOND PhD programme, Pedro was a Policy Advisor on EU law for the President of Equipo Europa, a Europeanist and non-partisan youth association with the aim of promoting the European Union among young people and encouraging youth political participation, and was part of the United Nations and International Law Society of Carlos III University (ANUDI), being the first director of "El Relator", a university legal journal focused on International Law and International relations, apart from doing a few internships in various law firms and the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture.

His academic interests are centred on various areas of EU law: the constitutional aspects of the Union´s law; the connection between EU and national law, the construction of the EU polity, the rule of law, the general principles and the protection of fundamental rights among others; the Law of the Economic and Monetary Union, including the banking union, the Law of the Common Commercial policy and International Trade and Investment Law.

My joint PhD is carried out between Luiss Guido Carli University and iCourts – Centre of Excellence for International Courts at the University of Copenhagen. During the final year of the fellowship, I undertook a professional research stage at the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) in Brussels, further connecting my academic research with policy and practice.

As part of my doctoral training and scholarly development, I have actively participated in numerous international conferences, doctoral seminars, workshops, and summer schools, including:

- EU Doctoral Seminar on European Constitutional Identity, Vienna University of Economics and Business (May 2025)

- Annual GEM-DIAMOND Conferences: Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne (Feb 2025), LUISS Rome (Mar 2024), Brussels (Mar 2023)

- Conference on the GEM-DIAMOND Edited Volume, Université de Genève (Jan 2025)

- Workshops on Dissensus over Liberal Democracy and the GEM-DIAMOND Handbook, ULB Brussels (Oct 2023, Oct 2024)

- ICON·S Annual Conference, IE University, Madrid (July 2024)

- GEM-DIAMOND Summer School, ULB Brussels (June 2024)

- Online Conference on Separation of Powers, University of Amsterdam (June 2023)

- 2nd Methods Workshop, University of Amsterdam (June 2023)

- iCourts PhD Summer School, University of Copenhagen (June 2023)

- YELS Conference, Maastricht University (June 2023)

- EUIA Conference, Brussels (May 2023)

- 2nd Citizen Innovation Lab on Impact and Social Science, ULB Brussels (May 2023)

- Interdisciplinary Methods Workshop, University of Copenhagen (April 2023)

- ICON·S Writing School (Feb–Mar 2023, hybrid format)

- AGORA Forum, Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca (Jan 2023)

- Kick-Off GEM-DIAMOND Conference, ULB Brussels (Oct 2022)

These activities have allowed me to present my work, receive feedback from leading scholars, and strengthen the interdisciplinary and comparative dimensions of my research on constitutional pluralism, judicial review, and EU integration.

-

Revisiting Madrid: Personal Reflections and Academic Debates at the ICON·S 2024 Annual Conference

18 July 2024

A GEM-DIAMONd fellows impressions from the 10th Annual Conference of the International Society of Public Law (ICON·S)

-

Making Sense of the Growing Use of Litigation Over the Fundamental Values of the European Union

21 September 2023

Some Ideas for Research Agenda Combining Doctrinal Law and Empirical Legal Studies

-

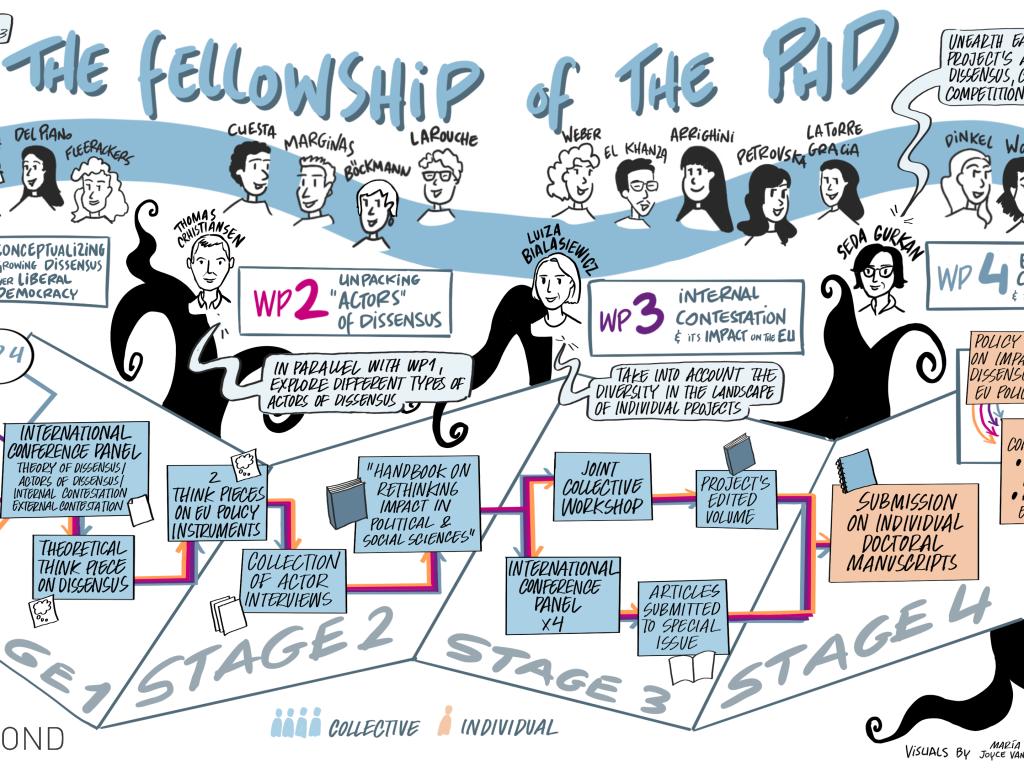

Birth of the GEM-DIAMOND Fellowship of the Ph.D.

1 October 2022

16 MSCA Fellows successfully selected following a gruelling selection process.