Édouard Hargrove

GEM-DIAMOND doctoral fellow

ESR 1 – Dissensus over the Rule of Law in Transnational Parliamentary Arenas: The case of the European Parliament

My research explores the more human, down-to-earth aspects of our grand debates over the meaning of liberal democracy in Europe.

Dissensus over the Rule of Law in Transnational Parliamentary Arenas: The Case of the European Parliament

Supervisors

- Ramona Coman

- Didier Georgakakis

Research abstract

Such legislative activity around meta-political issues—those that revolve around the very meaning of democratic politics— raises many interesting questions for social scientists. Adopting a more sociological perspective, the thesis begins with the classical question of who, in fact, are the politicians that specialise on these issues. Do they develop an interest for these topics because of previous experiences, tied to their political careers, their professional backgrounds, or perhaps their personal life stories? Or does their interest result from particular socialisation processes within the parliament itself? All of this leads us to consider the social trajectories of these politicians, but also the particular worth that they might attach to this committee and issue-set. Much like those who sit on the committee on foreign affairs (AFET), or the committee on constitutional affairs (AFCO), the ones who end up joining LIBE may view it as a particularly prestigious and desirable place to be. Some influential members of the parliament have indeed been a part of it, including those who went on to become vice-chairs of political groups, quaestors, and even president of the European Parliament (Martin Schulz and Roberta Metsola), while other members have built most of their in-parliament careers around it.

An emphasis on the social characteristics of politicians also opens up a distinct viewpoint on their social practices. How do politicians make decisions? Why do they prioritise certain issues over others? In other words, what is it that conditions their work, their parliamentary activity? Many scholars tend to examine the things that politicians do in relation to their ideological beliefs or partisan affiliations. While this approach does provide some insights, it neglects the more taken-for-granted, human aspects of their activities. When we start to look closer at them, some common patterns of behaviour tend to emerge around various norms and rules which politicians must learn and conform to. Much like in the Council of Europe, for example, these politicians tend to privilege a rather technical and diplomatic style of writing, as opposed to a more value-laden and straightforward political tone. Their legislative output remains political, but in a rather intricate and euphemistic way. The political issues at stake often take the form of specific wordings, (in)conspicuous omissions, or subtle variations. In a similar vein, these politicians are meant to relate the specific issues within individual member states to a more general set of cross-cutting "European" issues, lest they be accused of parochialism or portrayed as disruptive. Unlike in some national parliaments, politicians must adopt a more respectful and constructive approach towards others, who must be treated as colleagues instead of opponents. As for the inevitable debates and political disagreements that do come up, these must be dealt with using reasoned facts and sophisticated value judgements, rather than polemical rhetoric or crude opinions.

These questions feed into their work inside the committees, which is rather broad but also ambivalent. What is it that these politicians actually do? What is the nature and the purpose of their work? In some ways, the social practices of these MEPs may resemble those of constitutional judges. There is the rather technical language of their resolutions, the numerous references to rulings from national and European courts, and the discursive appeals to political-legal principles of government. A number of them, at times, even refer to themselves as "guardians" of democratic values, which further elicits this comparison. The substance of their work can also resemble that of national representatives in a diplomatic forum, such as the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe or the General Assembly of the United Nations. The constant efforts to draw up large majorities, the measured, non-polemical tone of most resolutions, and the establishment of fact-finding missions, all seem to echo the dynamics of those entities. At times, their practices may even resemble those of advocates from civil society organisations. When politicians convene round tables with academics, collaborate with non-profit entities on expert reports, or hold public hearings with members of national governments, there is a genuine sense in which their work resembles that of democratic activists. All of this has to be squared, though, with the fact that these people are (also) elected representatives. They belong to national parties and political groups, with clear ideological leanings and specific partisan interests. So how do these politicians cope with the different aspects of their work? In what ways, and especially under what circumstances, does their work take the form of principled politics? And when, on the other hand, does it come closer to party politics? Unlike some other policy areas, it would be wrong to assume that their work is always political in the narrow, partisan sense of the term. Yet given the nature of these issues, and the various stakes tied to them, it would be equally problematic to dismiss their political dimension altogether.

These last remarks open up one of the main questions of my thesis around the democratic values which these politicians seek to strengthen through their work. When dealing with relevant issues, various politicians often claim that these values are—or else should be—consensual across European societies. The fact that they share some terms of reference, and some general, nebulous understanding of what democratic politics basically entails, does suggest this. A number of the resolutions in the LIBE committee, such as those tied to the annual reports of the European Commission and the EU's Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA), also tend to garner wide political support, which further supports this point. Having said this, the fact that these values have to be repeatedly asserted, and that various politicians do in fact disagree over their application if not their meaning and significance, suggests otherwise. So how much consensus is there really? And what is the nature of this consensus? When does it hold, and when does it not? This ambiguity surrounding the status of these "core" values ties into the question of their contestation. Whenever (or to the extent that) these values are consensual, then it is fringe politicians who instigate dissensus, by disputing or dismissing these values head on. But whenever (or to the extent that) these values are more elusive, dissensus might come about among a wider range of politicians, and for a more varied set of reasons.

My primary research interests lie at the nexus between law and politics. I am interested in a range of issues that are tied to a wide variety of actors including elected politicians, government officials, lawyers, judges, academics, and interest representatives. These issues include high-profile legal proceedings, constitutional review of legislation, judicial reforms, especially around the nomination of judges, and the work of professional associations representing legal practitioners, to name a few examples. I am also interested in the politics of expertise, and especially the interstitial space of think tanks at the crossroads of different social fields.

⦿ March 2023: 1st annual conference of the GEM research program at the Free University of Brussels (ULB).

⦿ May 2023: 8th bi-annual edition of the European Union International Affairs (EUIA) conference at the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels.

⦿ November 2023: Symposium on current research of the Societies, Actors, Governments in Europe (SAGE) research centre at the University of Strasbourg.

⦿ March 2024: 2nd annual conference of the GEM research program at the Free International University of Social Studies (LUISS).

⦿ June 2024: 12th bi-annual edition of the Standing Group on the European Union (SGUE) conference of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) at the NOVA University Lisbon.

⦿ February 2025: 3rd annual conference of the GEM research program at the Sorbonne (Paris I).

⦿ June 2025: 1st edition in France of the Historical Materialism (HM) conference at Paris Dauphine University - PSL.

⦿ July 2025: Symposium on methodological approaches of the Societies, Actors, Governments in Europe (SAGE) research centre at the University of Strasbourg.

⦿ January 2026: Symposium on internationalisation processes in academic research of the European Centre for Political Science and Sociology (CESSP) in Paris (Pouchet / CNRS).

⦿ March 2026: 4th annual conference of the GEM research program at the Free University of Brussels (ULB).

Courses, Seminars & Workshops

⦿ October 2022-May 2023: Doctoral seminar, "Theory, Methodology, and Research in Political Science", at the Free University of Brussels (ULB).

⦿ February 2023: ECPR course, "Introduction to Social Network Analysis", at the Catholic University of Leuven (KU Leuven).

⦿ April 2023: First methodological workshop of the GEM research program at the University of Copenhagen (KU).

⦿ June 2023: Second methodological workshop of the GEM research program at the University of Amsterdam (UvA).

⦿ July-August 2023: MOOC courses (edX), "Statistics 1.1" and "Statistics 1.2" taught by Professor James Abdey (LSE).

⦿ September 2023-June 2024: Doctoral seminar, "Mobilisations conservatrices: idées, acteurs, circulations transnationales" at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS).

⦿ September 2023-ongoing: Monthly seminar of the European Centre for Sociology and Political Science (CESSP) at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS).

⦿ January 2024-ongoing: Writing workshops of the European Centre for Sociology and Political Science (CESSP) in Paris (Pouchet / CNRS).

Teaching Activities

⦿ January-May 2024: Teaching assistant for an undergraduate course (Y2), "Introduction à la politique européenne", at the Sorbonne (Paris I).

⦿ January-May 2025: Teaching assistant for an undergraduate course (Y2), "Introduction à la politique européenne", at the Sorbonne (Paris I).

⦿ September-December 2025: Teaching assistant for an undergraduate course (Y2), "Sociologie historique et politique de l'Union européenne", at the Sorbonne (Paris I).

-

The Prefigurative Politics of Research Software

4 April 2024

An appeal for the widespread adoption of free and open-source software in academia

-

Is there A Tribe Called Quant?

21 November 2023

Some reflections on the nature of the divide between quantitative and qualitative research in the social sciences.

-

The First Annual Conference

17 April 2023

The fellows present their research for the very first time, coupled with panels on the concept of dissensus and Prof. Petra Bárd’s keynote address.

-

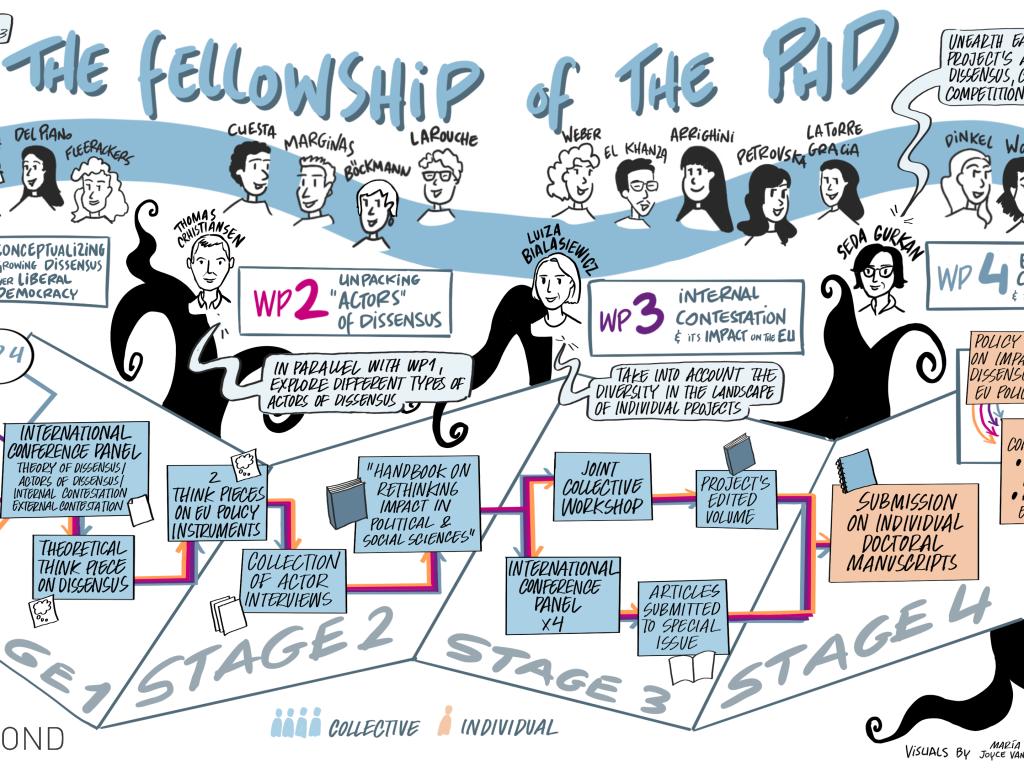

Birth of the GEM-DIAMOND Fellowship of the Ph.D.

1 October 2022

16 MSCA Fellows successfully selected following a gruelling selection process.